Market Politics

The Senate adopted a bipartisan infrastructure bill that outlines $550B in new infrastructure spending. After decades of talk, and failed attempts by governments led by both sides of the aisle, this newly passed infrastructure spending bill is one the likes of which we have not witnessed in most of our lifetimes. While people may have an objection to individual parts of the bill, the lion-share of the funds are earmarked for improvements which theoretically should benefit all Americans, and aid America in maintaining our seat as the dominant world power.

About two-thirds of the bill, $300 billion, is designated for improvement of roads, bridges, highways, public transit, passenger and freight rail, airports, as well as improving the nation’s power grid and water supply. The remaining third or so of the bill, ~$200 billion, will be invested in upgrading the security systems of various networks to help protect against cyberattacks, such as what we witnessed with Dominion Energy and natural disasters. Additionally, this money would also target improving and expanding the nation’s broadband infrastructure, which as we all witnessed this year, was vital in our nation’s ability to go through a lockdown and still maintain our businesses.

This is hardly the first time that America has doubled down on the deficit in order to improve the country and rebound stronger than ever. In 1862, burdened with debt and during a civil war, the US passed the Pacific Railway Act which provided government funds for rail companies to connect the two coasts, improving commerce, travel, and information flow which helped unlock the country’s potential for the next handful of decades. Similarly, in the late 1950s and early 1960s, coming off the tails of WWII and the Korean War, America spent billions on infrastructure spending for projects such as the interstate highway, the creation of NASA, Advanced Placement testing in schools, and railways (which planted the seeds for the creation of Amtrak).

Despite this bill being pared down from what Biden and the Democrats tried to get, the price tag for already approved improvements is nonetheless mind-boggling. Moreover, additional spending plans are still on the docket for debate! Fears about the budget are certainly warranted. However, a potential salve is that with interest rates so low, the U.S. can essentially enter a carry trade and simultaneously stimulate the country while also improving it.

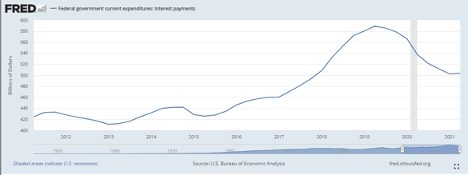

A carry trade is when we borrow at a low-interest rate and invest in an asset that provides a higher rate of return. Despite a much larger debt burden, the interest that the U.S. has needed to pay on said debt, is about the same amount as the interest paid back in late 2017, early 2018.

(Courtesy: fred.stlouisfed.org)

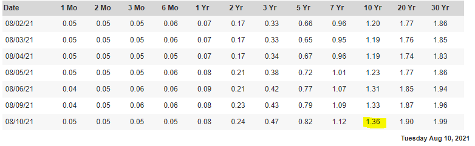

Current Treasury Yields

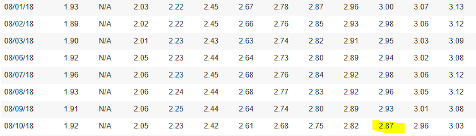

Treasury Yields in August 2018

(Courtesy treasury.gov)

As a thought experiment let us assume that the Democrats and Republicans magically agree on everything and pass unedited the proposed $3.5T spending bill (gasp, politicians getting along!) and calculate the interest costs of the bill. Above are the current treasury yields, and the yields on the same instruments if you were buying them in August of 2018. If for example, the government pays the spending bill using 10-year Treasuries, the yield was 2.87% on August 10, 2018, meaning interest on that would be: $3.5T x (2.87%)= $0.1005T or about $100B. Currently, the interest on that same spending bill would only cost ($3.5T x (1.36%))= $0.0476T or about $48B. Theoretically America could go crazy and make a $7T spending bill and at these current interest rate levels pay the same amount of interest as we would have for a $3.5T bill back in 2018!

Of course, all bills come due at some point, so it is important to make sure the payment section of the proposed bill checks out. Being able to push these expenses to the longer end of the Treasury curve provides the U.S. with the time to not only complete the projects, but also give us all the necessary time to start enjoying the benefits from these improvements. Moreover, it increases the margin for error regarding the forecasted revenues generated from these projects. If, the U.S. paid for this infrastructure spending with 1-Yr Treasuries, the government would have to be incredible accurate with the forecasted revenues generated from these projects. For the past initiatives mentioned above, the U.S. did not make their money back the following year, or next couple years. However, over the course of many years and decades, these bills helped bolster U.S. growth and empower the U.S. to achieve firsts that no-one else had before.